Space jam: As the threat of orbital debris rises, so are efforts to reduce space junk

June 6, 2024 | By Enrique Segura

Traffic cops … in space?

Commercial flights into low Earth orbit are taking off, more satellites are launched each year (2,166 from the U.S. alone in 2023), and new space capabilities are emerging, such as in-orbit robotic manufacturing. The problem isn’t necessarily the volume of spacecraft, though — it’s the mess they leave behind.

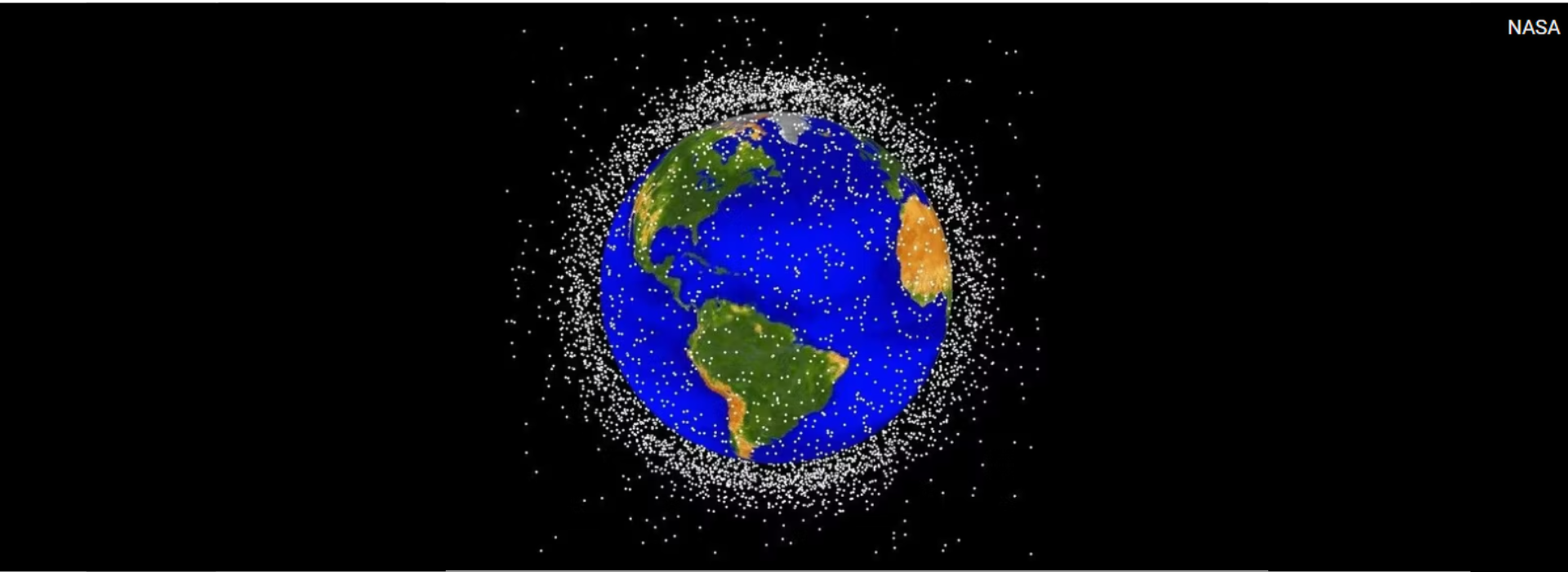

Space debris is essentially orbital roadkill. There are thousands of defunct spacecraft and rocket bodies and millions of pieces of space junk orbiting Earth at thousands of miles an hour, according to a recent National Geographic story. It has damaged satellites, threatened spacewalks and even created havoc on Earth — in March, a pallet filled with spent nickel-hydrogen batteries, discarded by the International Space Station in 2021, smashed through the roof of a Florida home.

Out of this ‘wood’

In an effort to mitigate the increase of junk above the stratosphere as the space industry continues to expand, Kyoto University and Sumitomo Forestry announced last week the completion of LignoSat, the world’s first wooden artificial satellite.

LignoSat will launch in September from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida to the International Space Station, with a further deployment from the station’s Japanese Experiment Module Kibo one month later.

At the start of the project, researchers first sent to space wooden samples, including magnolia, cherry and birch, for tests, selecting magnolia, sourced from Sumimoto Forestry’s company forest, as the winning candidate for its stability and lightness.

LignoSat is a box the size of a coffee mug with wooden panels less than half an inch thick over an aluminum frame. The cube was assembled using a traditional Japanese technique called sashimono, which assembles wooden items without nails by employing complex wood joints. This approach ensures that the pieces fit together perfectly, and this construction won’t affect radio transmission or mechanical equipment when in use at the station.

“When you use wood on Earth, you have the problems of burning, rotting and deformation, but in space, you don’t have those problems,” Koji Murata, a researcher at Kyoto University, told CNN. “There is no oxygen in space, so it doesn’t burn, and no living creatures live in them, so they don’t rot.”

When the LignoSat reaches the end of its mechanical life, it will descend into the atmosphere and burn, leaving only biodegradable ash. Traditional metal satellites can create air pollution risks during re-entry. This could be a major breakthrough for finding creative solutions that consider both the performance and the environmental impact of the materials used.

During its six-year mission, the satellite will report on wood expansion, contraction and how it withstands heat. Its design will also test if wood can be used for structural purposes in space. This data later will be used by the Kyoto University’s communications station for the development of a second satellite, the LignoSat-2.

“Expanding the potential of wood as a sustainable resource is significant,” Takao Doi, a Kyoto University professor and astronaut, told The Japan Times. “We aim to build human habitats using wood in space, such as on the moon and Mars, in the future.”

Sustainability in space

Meanwhile, space agencies are working to prevent more debris from being created and to find innovative ways to clean up the thousands of tons of space junk already in orbit.

Last month, a dozen countries signed on to the European Space Agency’s Zero Debris Charter, a non-binding agreement to limit the creation of orbital debris. In April, NASA released the first part of its Space Sustainability Strategy, which includes plans to identify breakthrough methods to sense and predict risks in operating around space debris and finding cost-effective ways to reduce the creation of new debris.

“Space is busy — and only getting busier,” Pam Melroy, NASA’s deputy administrator, said in a statement. “If we want to make sure that critical parts of space are preserved so that our children and grandchildren can continue to use them for the benefit of humanity, the time to act is now.”

Banner photo: Low earth orbit, the region of space within 1,200 miles of the Earth's surface, is the most concentrated area for orbital debris. (Image credit: NASA Orbital Debris Program Office)